First drugs ever approved for lupus nephritis

A decade ago, transplanting a kidney from a hepatitis C-positive (viremic) donor into a hepatitis C-negative recipient would have been unthinkable.

A decade ago, transplanting a kidney from a hepatitis C-positive (viremic) donor into a hepatitis C-negative recipient would have been unthinkable.

Reem Daloul, MD, transplant nephrologist in The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Division of Nephrology, says curative treatments for hepatitis C have made use of hepatitis C-viremic organs a viable option for non-infected recipients.

At the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, Dr. Daloul adds, this practice has become standard of care. The team has now safely and successfully transplanted more than 100 hepatitis C-viremic kidneys into HCV-negative patients in need of a transplant.

What started in 2019 through a 30-patient clinical trial has been expanded to include those in need of multi-organ transplants, including kidney/pancreas and kidney/liver.

“We expected good outcomes from our study, but we had excellent outcomes,” says Dr. Daloul, who served as principal investigator for the Use Hep-C, Utilization of Hepatitis C Positive Kidneys in Negative Recipients study. “The patients we’ve liberated from dialysis through this advanced approach to transplant care are very appreciative for the opportunity.”

While the use of hepatitis C-viremic kidneys is becoming routine at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, the practice has yet to become standard at most transplant centers across the country.

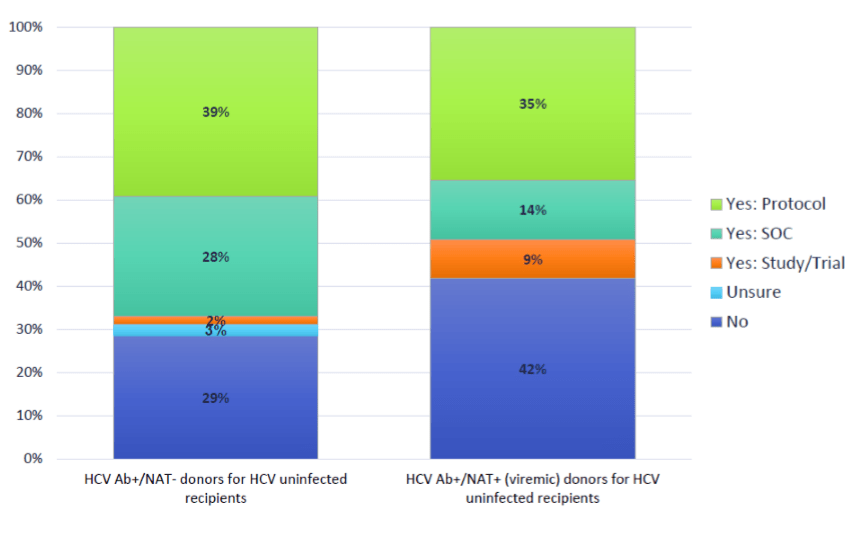

A 2019 national survey of transplant clinicians found that 42% of U.S. transplant centers do not perform kidney transplants from HCV-viremic donors (hepatitis C-positive donors) into negative recipients.

A 2019 national survey of transplant clinicians found that 42% of U.S. transplant centers do not perform kidney transplants from HCV-viremic donors (hepatitis C-positive donors) into negative recipients.

Dr. Daloul says insurance coverage could be one barrier to making this approach the standard-of-care nationwide.

“Early on in our study, we had to deal with a lot of pushback from payers who refused to cover the therapy needed to make this type of transplant successful,” Dr. Daloul says. “As we began doing more and more of these procedures, we were able to educate insurers about the safety of this treatment option, which has made it much easier for us to get the drug therapy covered.”

Dr. Daloul says adding hepatitis C-positive organs to the donor pool is one critical step toward reducing transplant wait time and saving more lives.

July 2021 data from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) showed nearly 90,000 people on the waiting list for a kidney transplant. In 2020, 22,817 kidney transplants were completed — both living and deceased.

“This represents a big gap between those in need and what’s available,” Dr. Daloul says. “Every single extra donor we can add to the pool is another eight lives saved.”

Identifying viable donors

In many cases, hepatitis C-viremic organs come from donors who die from drug intoxication.

“Despite significant efforts to combat the opioid crisis, deaths related to drug intoxication continue to rise,” Dr. Daloul says. “Many of these potential donors might also have hepatitis C, but with the proper care and follow-up, these organs can be viable transplant options.

“Centers like ours have infrastructure and clinical expertise in place to ensure safe and successful treatment and long-term management for those transplanted with hepatitis C-viremic organs.”

Dr. Daloul and team recently completed study follow-up and published their findings.

They are also eyeing the next phase of their research work, which includes evaluation of any association between hepatitis C and other post-transplant viral complications. They will also review data for post-transplant development of donor-specific antibodies.