A common complication of retinal detachment surgery or certain ocular injuries is proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR), a form of scarring that can lead to vision loss and even blindness. A team at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center has been studying cellular mechanisms and signaling involved in the development of PVR, and it has identified several signaling pathways — as well as drugs that could eventually be used for treatment and prevention.

A common complication of retinal detachment surgery or certain ocular injuries is proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR), a form of scarring that can lead to vision loss and even blindness. A team at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center has been studying cellular mechanisms and signaling involved in the development of PVR, and it has identified several signaling pathways — as well as drugs that could eventually be used for treatment and prevention.

New approach to a longstanding problem

Incidence of PVR is 5-10% following retinal attachment surgery and is common after penetrating or perforating ocular injuries affecting the back of the eye. As the scar forms and contracts, the retina becomes distorted from folds or detachment of the retina, which can lead to loss of visual acuity. Surgical correction often fails, and recurrence is high as the mechanisms of this uncontrolled scarring remain a challenge. Many patients suffer permanent vision impairment.

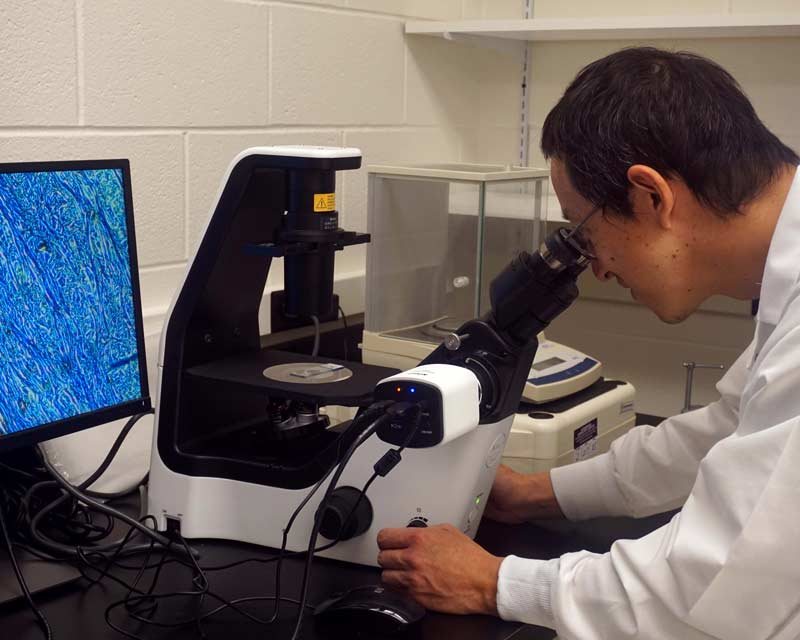

Research targeting proliferation of cells involved in PVR has not shown much success, so Dr. Tamiya focused on other aspects of scarring. His team has honed in on a process of transdifferentiation of ocular cells to a myofibroblast, which is a type of cell that specializes in extracellular matrix production, modification and subsequent contraction. His team has identified several important signaling pathways with druggable targets that can possibly be used for treatment. The team is using in vivo pig models to test potential therapeutic agents for PVR. The most promising so far is dasatinib, a drug marketed as Sprycel by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

“This drug is used to treat a specific type of leukemia, but it also prevents multiple cell functions associated with scarring and contraction with minimal toxicity,” Dr. Tamiya says. “Side effects, if any, in our pig models are not detectable.”

Another challenge is drug delivery, which is an injection into the eye. Dr. Tamiya and his team are working on a sustained release system to prevent the necessity of reinjection, and it has already shown success in pig models.

“Further research into the mechanisms involved in scarring and contraction could help identify more promising targets and potential drugs,” says Dr. Tamiya. He’s leading this effort and is hopeful that his work will result in more therapeutic options and better outcomes for patients to prevent PVR-related vision loss.

“Prevention of PVR is the goal, but even significant delay of early fibrotic changes will allow more treatment options,” Dr. Tamiya says. “It could also open the window on timing of surgical intervention.”

Feedback from ophthalmologists is vital. “We would love to hear from the surgeons who perform retinal detachment surgery and whose patients could benefit dramatically if we could prevent or delay PVR and the associated vision loss,” says Dr. Tamiya.