Novel health services research underway at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center may reveal whether prostate fibrosis contributes to the development and progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and whether antifibrotics can improve BPH-related lower urinary tract symptoms.

Novel health services research underway at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center may reveal whether prostate fibrosis contributes to the development and progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and whether antifibrotics can improve BPH-related lower urinary tract symptoms.

By analyzing health insurance claims data for men with symptomatic BPH, endourologist and principal investigator Matthew Lee, MD, can compare outcomes among those treated with standard medical therapy and those taking antifibrotics for other medical conditions.

Dr. Lee’s efforts could pave the way for further research in this area, including randomized, controlled clinical trials. Should antifibrotics prove to be a safe, effective treatment for prostate fibrosis and BPH, it could give millions of patients a new – and noninvasive – option for managing frustrating symptoms.

Exploring a new class of medications to treat BPH symptoms

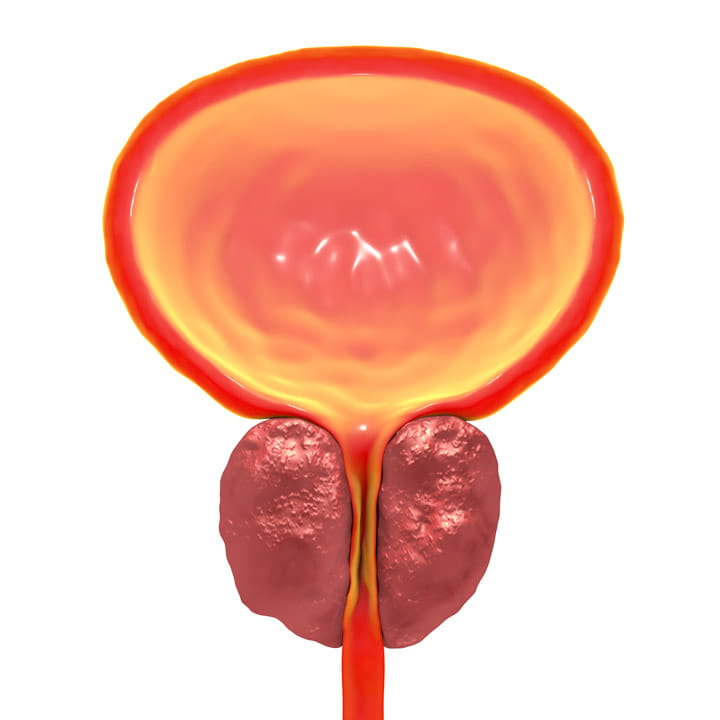

Benign prostatic hyperplasia affects more than half of men over age 50, causing symptoms such as incontinence, urinary frequency or hesitancy, nocturia and incomplete emptying of the bladder.

Although nonsurgical treatments exist, they don’t work for every patient; studies show around 5% of men on maximum medical therapy still experience clinical progression of symptoms. For this subset of patients, surgery is the only remaining treatment option.

“There are a limited number of medical therapies for BPH, including alpha blockers and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, and we’ve been using them for decades,” Dr. Lee says. “When these treatments aren’t effective, persistent symptoms can lead to complications ranging from recurrent urinary tract infections to kidney failure. And although surgery can improve symptoms and prevent complications, it poses short- and long-term risks, including erectile dysfunction, retrograde ejaculation and loss of bladder control.”

It’s long been thought that BPH-related urinary symptoms occur because of the increasing size of the prostate gland and/or prostate muscle tension. However, some preclinical research suggests BPH progression – and subsequent worsening symptoms – may also be caused by prostate fibrosis. And there aren’t any therapies approved to treat prostate fibrosis.

“Researchers have found that antifibrotics improve lower urinary tract symptoms in animal models of BPH,” Dr. Lee says. “But these drugs, including pirfenidone and lenalidomide, haven’t been studied in humans with symptomatic BPH. And we can’t conduct clinical trials until we have more data.”

Using claims data to confirm preclinical data

To generate the data necessary for additional research, Dr. Lee and his colleagues are mining a commercial database containing de-identified health information for tens of millions of patients covered by Medicare, Medicaid or private insurance.

Using ICD-10 codes, they identified a cohort of men who’ve been diagnosed with lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to BPH. This cohort includes an experimental group (patients who have medical conditions requiring antifibrotic therapy) and a control group (patients undergoing traditional medical therapy for their urinary symptoms who haven’t been exposed to antifibrotics).

The research team aims to determine rates of BPH treatment success and failure among both groups by comparing the number of patients who discontinued medical management for their urinary symptoms and the number of patients who had surgery to treat their symptoms.

“In this instance, there are several benefits to using claims data to validate preclinical data,” Dr. Lee says. “Not only does the database provide a large, statistically significant sample size, it also allows us to track real-world outcomes. And perhaps most importantly, we can capture clinical data without the expense of launching a clinical trial – and without exposing patients to potentially adverse side effects.”