Benjamin Segal, MD, chair of the Department of Neurology at The Ohio State University College of Medicine and director of the Neuroscience Research Institute at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, is leading initiatives that aim to dissolve boundaries between disciplines in translational neuroscience and accelerate the movement of discoveries from laboratory benches to clinical application. Within this culture, early-career investigators are pursuing studies that aim to impact treatment in the foreseeable future.

Across complex and insidious diseases such as multiple sclerosis, glioblastoma and stroke, young investigators are probing the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms and identifying novel targets for disease modification. Others are leveraging newly generated and real-world data to refine clinical measurements, standards and decision making. Together, their work reflects a pragmatic, impact-oriented approach to discovery. Here, we feature some of their promising work.

Recalibrating dural nociceptor activity sensitizes glioblastoma to immunotherapy

Research increasingly shows that glioblastoma evades immunotherapy not only through tumor-intrinsic mechanisms, but also through active suppression of immune responses by neural circuits within the central nervous system.

With support from a Pelotonia IRP Junior Investigator Award, The Block Memorial Lectureship Junior Faculty Award and an American Brain Tumor Association Discovery Grant, Nandini Acharya, PhD, is investigating how neuropeptides influence antitumor immunity in glioblastoma.

With support from a Pelotonia IRP Junior Investigator Award, The Block Memorial Lectureship Junior Faculty Award and an American Brain Tumor Association Discovery Grant, Nandini Acharya, PhD, is investigating how neuropeptides influence antitumor immunity in glioblastoma.

“We still have an incomplete understanding of how immune niches across the central nervous system – or CNS – coordinate antitumor responses. Until we define those principles, we cannot fully leverage immunotherapy for glioblastoma,” Dr. Acharya says.

Using longitudinal immune profiling in mouse models of glioblastoma, her team tracks how immune responses evolve across distinct CNS compartments over time. By comparing tumors that respond to immunotherapy with those that are resistant, they have shown that surrounding tissues – not just the tumor itself – play a major role in shaping immune outcomes. This work has highlighted the meninges as a key site of immune regulation and identified sensory nerves, particularly nociceptors in the dura, as important upstream modulators of these responses.

Dr. Acharya’s group has further demonstrated that calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), a neurotransmitter released by these sensory nerves, directly suppresses antitumor immune activity. In response to signals from glioblastoma cells, meningeal sensory nerves release CGRP, which diffuses into the tumor and alters the behavior of tumor-associated macrophages. By activating CGRP receptors on these immune cells, CGRP drives them toward an immunosuppressive state, weakening T-cell-mediated tumor control and allowing tumor growth to continue.

“We’ve shown that glioblastoma hijacks nociceptive sensory neurons to suppress immunity, and that nociceptor-derived signals are a key driver of the formidable immunotherapy resistance seen in this disease,” she says.

Together, these findings reveal a previously underappreciated neuro-immune pathway that may help explain why immunotherapy has been largely ineffective in glioblastoma – and suggest new therapeutic strategies that target neural signaling to restore antitumor immunity. These include drug repurposing with already-approved CGRP-pathway inhibitors (for migraine) to enhance anti-glioblastoma immune responses, and circuit control by silencing or ablating nociceptors (through targeted blocks or neuromodulation) to remove the upstream driver of suppression.

“Deployed under a biomarker-guided framework, these complementary strategies are designed to shift glioblastoma from immune-refractory to immunotherapy-responsive, with a clear line of sight to early clinical testing,” Dr. Acharya says.

Building on these insights, her research program not only aims to reshape and augment antitumor immune responses, but also aims to advance next-generation biomarkers and define druggable targets that recalibrate immunity.

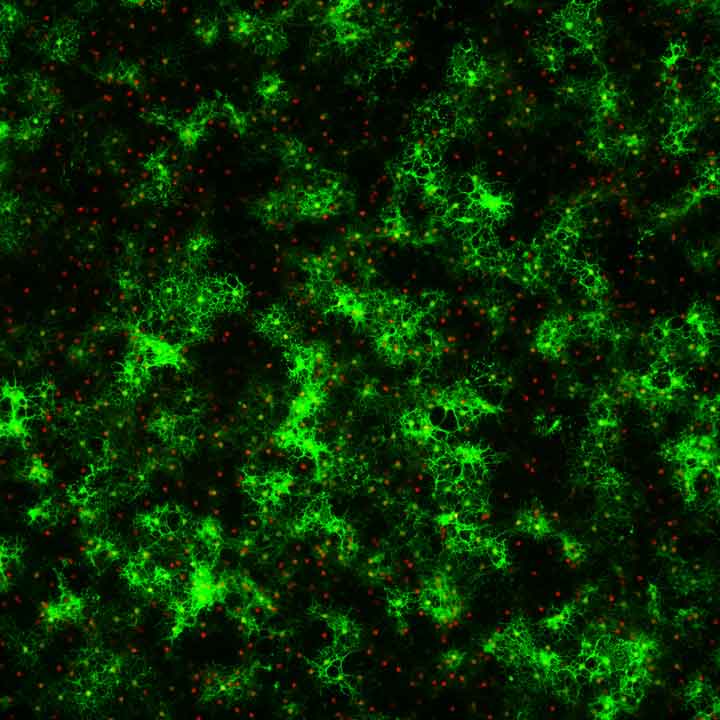

Left image: Meningeal tertiary lymphoid structures in GBM-bearing mice. Representative whole-mount immunofluorescence image of the meninges showing a tertiary lymphoid structure composed of B220⁺ B cells and CD3⁺ T cells, with CGRP⁺ sensory nerve fibers traversing the meningeal tissue.

Center image: In vitro–cultured sensory neurons. Representative immunofluorescence image of trigeminal ganglion (TG) neurons cultured in vitro and stained for TUJ1 (βIII-tubulin), highlighting neuronal cell bodies and extensive neurite outgrowth characteristic of nociceptive sensory neurons.

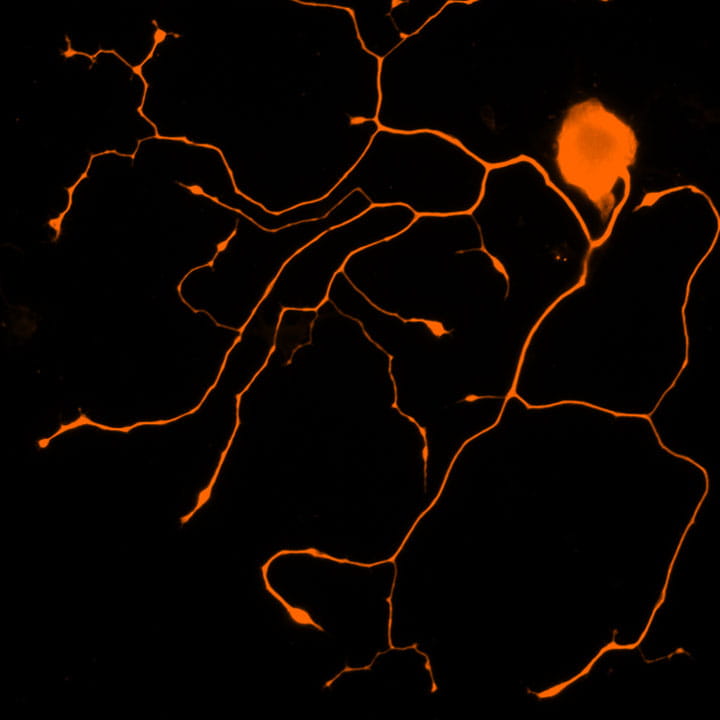

Right image: Sensory nerve fiber innervation of the meninges. Representative whole-mount immunofluorescence image of the meninges showing an extensive network of CGRP⁺ sensory nerve fibers distributed throughout the meningeal tissue, highlighting dense sensory innervation within the meningeal compartment.

Protective subsets of oligodendroglia spark hopes for remyelination in MS

With support from an American Academy of Neurology Career Development Award and a Department of Defense Exploration/Hypothesis Development Award, Cole Harrington, MD, is studying oligodendrocytes – the cells responsible for myelinating axons in the central nervous system – within the inflammatory environment of multiple sclerosis (MS).

With support from an American Academy of Neurology Career Development Award and a Department of Defense Exploration/Hypothesis Development Award, Cole Harrington, MD, is studying oligodendrocytes – the cells responsible for myelinating axons in the central nervous system – within the inflammatory environment of multiple sclerosis (MS).

Historically, immune signaling has received limited attention in oligodendrocyte biology. Dr. Harrington’s work challenges this view by identifying pathways within oligodendrocytes that appear to limit inflammation and support cell survival. Their goal is to define mechanisms that could be harnessed to promote remyelination and axonal repair in MS.

“Because inflammation can inhibit remyelination, mouse models are typically built to lack a strong immune response,” Dr. Harrington says. “Yet inflammation is central to MS, so my models have an inflammatory environment consistent with MS.”

While loss of oligodendrocytes and their myelin sheaths underlies demyelination in MS, Dr. Harrington found that certain oligodendrocyte subsets may play an unexpectedly protective role in the presence of inflammation. These cells activate genes and proteins that allow them to communicate directly with T cells and other immune cells, potentially helping to restrain damaging immune responses.

This new understanding of the protective responses of oligodendrocyte subsets could lead to new drug targets.

“Our overall goal is to develop therapies that could be used at the time of an acute relapse to improve recovery and potentially even during the course of MS to reduce disability,” Dr. Harrington says. “My hope is that a drug that simulates or stimulates the protective response of oligodendrocytes may serve as a powerful therapy.”

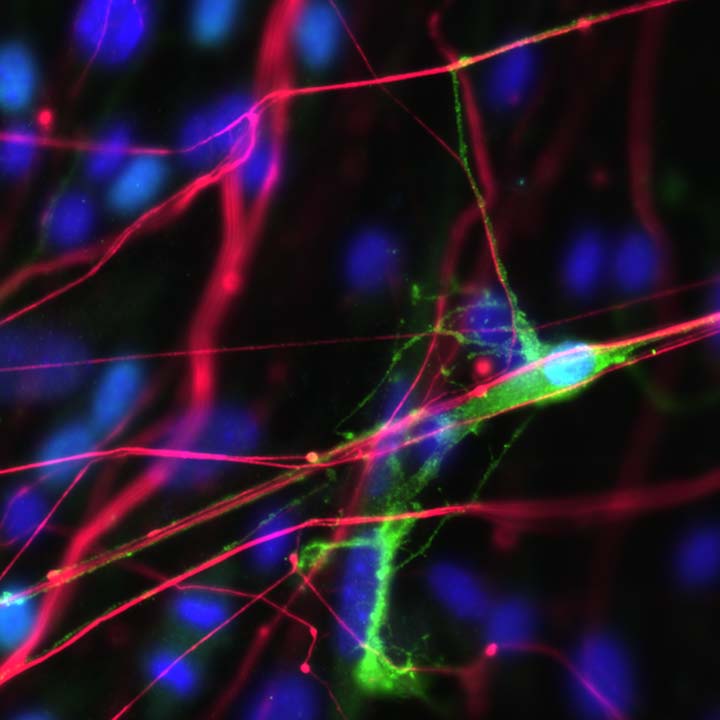

Left image: Mature oligodendrocytes grown in culture (myelin MBP+ processes green, Olig2+ cell bodies red).

Right image: Myelinating oligodendrocyte (GFP, green) reaching out to wrap and contact an axon (NF, red) grown in culture.

Exploring links between multiple sclerosis and accelerated aging

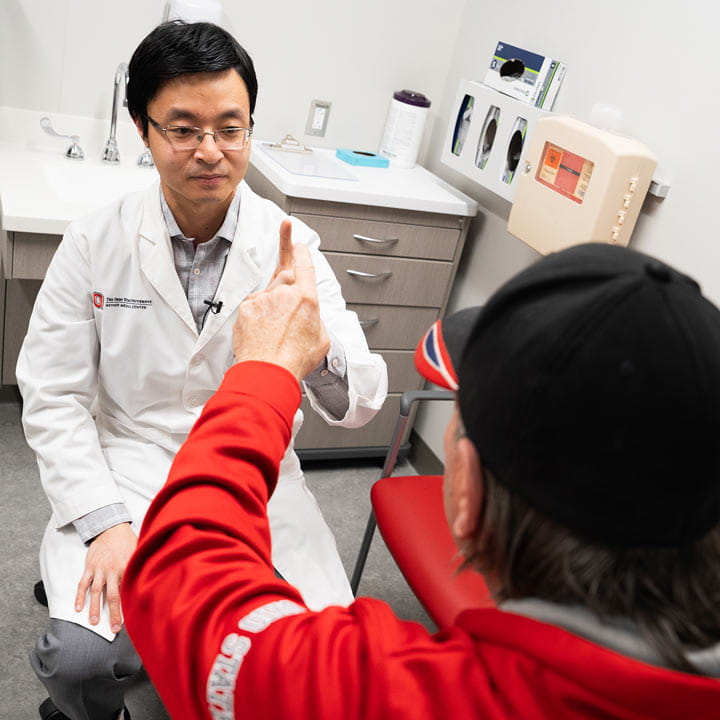

Yinan Zhang, MD, is examining how immune dysfunction and disease progression in MS intersect with biological aging. His work focuses on whether accelerated biological aging contributes to the development of secondary progressive MS (SPMS), which often emerges after years of relapsing-remitting disease.

Yinan Zhang, MD, is examining how immune dysfunction and disease progression in MS intersect with biological aging. His work focuses on whether accelerated biological aging contributes to the development of secondary progressive MS (SPMS), which often emerges after years of relapsing-remitting disease.

Supported by a National Institute on Aging K23 Career Development Award from the NIH, Dr. Zhang applies concepts from geroscience to the interpretation of patient-derived clinical and immune marker data. He is one of a small number of clinician-scientists using insights from aging biology to better understand the pathogenesis of progressive MS.

Advancing age carries the highest risk for developing treatment-resistant SPMS, yet the cellular, molecular and genetic processes that link biological aging to MS progression remain poorly defined. The emerging interdisciplinary field of geroscience provides an opportunity to understand diseases from the perspective of biological aging.

In his current work, Dr. Zhang is using established markers of cellular aging – such as p16^INK4a – and age-related epigenetic measures, referred to as “epigenetic clocks,” to study how biological aging influences MS outcomes. Building on an initial study funded by a National Institute on Aging GEMSSTAR award that quantified biological aging in people with MS, he is now conducting a two-year longitudinal analysis to examine how these aging measures relate to disease progression and clinical outcomes.

“Our vision in creating the framework for future studies is twofold. First, we foresee biological aging serving as a prognostic biomarker in MS, toward offering early aggressive treatment of MS in individuals with accelerated biological aging,” Dr. Zhang says. “Second, our platform will enable researchers to conduct trials of anti-aging therapies in combination with MS disease-modifying therapies to mitigate or even prevent MS progression.”

Image above: Yinan Zhang, MD, examines a patient with multiple sclerosis at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center.

Cerebral autoregulation and blood pressure management after intracerebral hemorrhage

Neurointensivist and vascular neurologist Mohamed Ridha, MD, studies the difficult challenge of blood pressure management following intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). In the acute setting, lowering blood pressure is critical to reduce the risk of hematoma expansion and improve functional outcomes, yet determining the optimal target for individual patients remains an ongoing clinical challenge.

Neurointensivist and vascular neurologist Mohamed Ridha, MD, studies the difficult challenge of blood pressure management following intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). In the acute setting, lowering blood pressure is critical to reduce the risk of hematoma expansion and improve functional outcomes, yet determining the optimal target for individual patients remains an ongoing clinical challenge.

Current guidelines promote a standardized approach to blood pressure reduction, but Dr. Ridha emphasizes that optimal targets may vary between patients. In those with long-standing or untreated hypertension – a common feature of intracerebral hemorrhage – aggressive blood pressure lowering may disrupt cerebral autoregulation, the process that normally safeguards the brain from hypoperfusion.

“The current targets do not account for the unique physiology of the cerebrovasculature to regulate blood flow,” he says. “In fact, applying the uniform BP-reduction approach may be a cause of cerebral ischemic injury in patients with impaired cerebral autoregulation.”

Dr. Ridha believes that incorporating measures of cerebral autoregulation into clinical decision making could enable personalized blood pressure targets and lead to better outcomes than current uniform approaches. Supported by an American Heart Association Career Development Award and an Ohio State College of Medicine Research Innovation Career Development Award, his work is helping lay the foundation for more individualized blood pressure management strategies.

In preliminary analyses from a large cohort of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage and untreated premorbid hypertension, Dr. Ridha demonstrated a measurable relationship between chronic hypertension control and the risk of cerebral ischemia associated with blood pressure–lowering interventions.

He says, “The question became, what should be the intensity of BP-lowering treatment for these patients, and should we individualize blood pressure targets for intracerebral hemorrhage patients?”

To address these questions, Dr. Ridha will reanalyze data from a prior randomized controlled trial and conduct a prospective pilot study examining the relationship between blood pressure reduction, baseline hypertension control and neurologic outcomes in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. In parallel, he will use cerebral oximetry in a pilot study to assess cerebral autoregulation in real time as blood pressure is lowered.

Using these data, he aims to develop individualized blood pressure targets based on each patient’s autoregulatory capacity and to test these personalized targets against current standard blood pressure goals in future studies.

“The overall goal is to provide a mechanistic explanation for heterogeneity in the effectiveness of uniform BP reduction and to use cerebral autoregulation data to inform an individualized approach to this intervention for ICH,” Dr. Ridha says.