Signs of appendicitis you shouldn’t ignore

You seem to hear about appendicitis all the time, but only about 5% of people get it. It’s most common in children, ages 10 to 19. It’s not hereditary or preventable. But when an appendix gets infected or bursts – causing appendicitis – you’re in trouble.

It’s a life-threatening emergency that you shouldn't ignore.

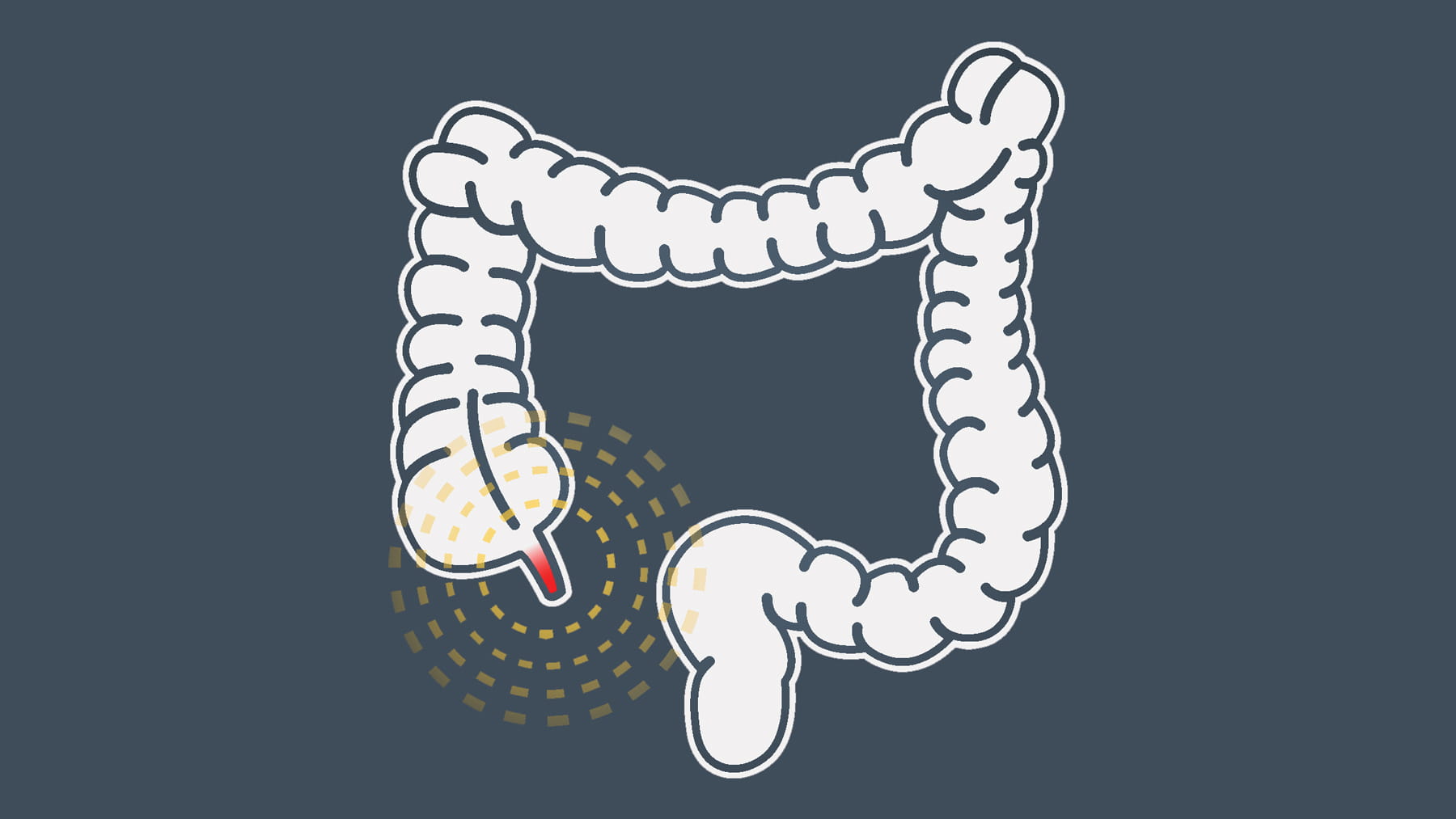

The appendix is an appendage that hangs off the beginning of the colon, or large intestine. It doesn’t have a function, and we all can live without it. If you take a balloon and poke your finger through it, that’s what the appendix looks like. It’s about the size of your little finger.

An appendix gets infected when there’s an obstruction in your large intestine. It gets blocked up, and an infection can occur. We don’t always know what causes it. In some cases, it’s due to feces getting into the appendix, which is located near where your feces transitions from a liquid to a solid, causing bacteria to multiply.

Appendicitis happens quickly – in some cases, several hours after the obstruction occurs. The earlier it’s treated, the better the outcome. If you get it treated quickly, within 12 hours, you’ll be in and out of the hospital within a day.

Because the appendix can rupture without treatment, everyone needs to recognize the warning signs of appendicitis, progressing from first to last:

- Sudden pain around the belly button or the upper abdomen – a gnawing, aching pain unlike anything you’ve ever felt

- Pain that intensifies over a couple of hours and migrates to the lower right abdomen (the area around right hip bone)

- A lack of energy and loss of appetite

- The condition progressively worsens, perhaps leading to nausea

- Constipation, inability to pass gas, or diarrhea

- A fever of 99-102 degrees

If the pain goes away, it’s likely not appendicitis. If not, and you find yourself at or near the bottom of the list, get to the hospital.

The standard treatment, as you probably already know, is an appendectomy, surgery to remove the appendix. It’s often performed to prevent the appendix from rupturing. After administering the patient antibiotics, the surgeon removes the appendix through three half-inch incisions.

Other options include laparoscopy, a fiber-optic instrument that’s used for viewing inside the abdomen and permitting a surgical procedure. The incision is smaller that way, and the recovery is faster. Another option being tested at Ohio State is the use of antibiotics instead of surgery.

Within a day, patients can get up and move around. They can resume normal activities in a couple of weeks.

What if you wait too long to seek help?

There’s a real problem in waiting too long to treat appendicitis. You might feel really bad, but suddenly feel better. This could occur when the appendix actually ruptures. About three hours later, you’ll get really sick because infection is freely floating around the belly. This situation can lead to sepsis, a possible life-threatening condition caused by the body’s response to an infection. Care becomes much more complicated, and you might find yourself being rushed to the hospital in an ambulance.

In this situation, an abscess forms where the appendix was, or the appendix freely ruptures in the abdomen. We’ll put a drain by the appendix to remove toxins. We don’t remove the appendix, because it can cause more harm. Patients might find themselves in the hospital for weeks.

We find the abscess, drain it and eventually send home patients on antibiotics. Eventually, about six months later, we’ll perform a laparoscopic appendectomy or a surgery called an interval appendectomy. Again, we administer antibiotics to fight possible peritonitis, or the infection of the abdominal cavity’s lining. General anesthesia is given, and the appendix is removed through a short incision in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen.

The bottom line is you don’t want to be in this situation. Don’t wait to get medical care if you notice potential signs of appendicitis.

David Renton specializes in minimally invasive surgery, including laparoscopic abdominal surgery, at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, where he’s also the chief of surgery at East Hospital.