Ohio State College of Medicine: Weeding out medical racism at its roots

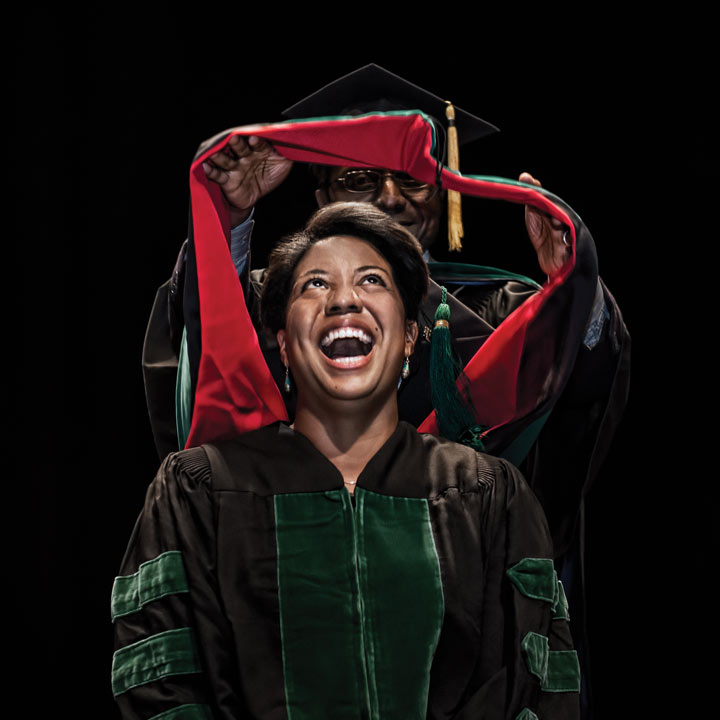

The Ohio State University College of Medicine is the seventh most diverse medical school in the nation — the highest ranking among top-40 research schools — according to U.S. News & World Report.

The Ohio State University College of Medicine is the seventh most diverse medical school in the nation — the highest ranking among top-40 research schools — according to U.S. News & World Report.

Outside of historically Black colleges and universities, the Ohio State College of Medicine’s percentage of Black students is among the highest in the nation at 13%, matching the Black population percentage in the United States.

The college has made tremendous progress attracting a high-achieving student body that’s diverse, and its holistic practices in admissions became ever more important as 2021 saw a 14% increase in College of Medicine applicants.

But in 2020, Ohio State College of Medicine faculty and leadership heard loud and clear — not just from the protests throughout the U.S., but also from our own students — that racial bias was far from eradicated in their worlds.

In response, the college formed an Equity and Anti-Racism Task Force, led by Jennifer McCallister, MD, associate dean for Medical Education, and Demicha Rankin, MD, associate dean for Admissions.

Drs. McCallister and Rankin say that the goal now isn’t just to get underrepresented students into the medical workforce, but also to give those students the support and resources they need to feel welcome, be successful in their careers and provide unbiased, high-quality health care.

Detailed initiatives

The college’s Equity and Anti-Racism Task Force, a multidisciplinary group of 10 faculty and seven students, first created guiding principles and action items that are now being implemented by newly formed workgroups. Their current aim: To carry out the goals of this new framework, aimed at quickly and broadly addressing the unique needs of medical students from backgrounds underrepresented in medicine, while supporting cultural competency for all.

The broad principles of the task force’s plan:

- Teach students, faculty and staff to intentionally and actively dismantle racism in medicine.

- Empower all students to be successful by building an infrastructure that is supportive of a diverse student body and marginalized individuals.

- Cultivate a strong sense of advocacy and a genuine sense of belonging within the College of Medicine for all students and particularly for students from marginalized communities.

- Collaborate within the College of Medicine to elevate our commitment to fostering health equity, diversity and inclusion.

“We’re now in a place where our sleeves are rolled up and we’re committed to this, and the university has committed the resources necessary to carry out our goals,” Dr. McCallister says. “We’re excited to see progress in these areas and we’re feeling unified forward action.”

Revising existing curriculum

The task force has developed and adopted new guidelines and tools to help College of Medicine faculty revisit and revise their curriculum through a modern, equitable and anti-racist lens.

“We’re humans. We all have experiences that influence our decisions, and we’re not trying to get rid of that — everyone’s experiences influence who they are. But we all have a responsibility to check our biases, especially in our professional and decision-making capacities.”

— Demicha Rankin, MD, associate dean for Admissions

To facilitate that work, the group completed a comprehensive mapping of all curriculum to examine how well it communicates unbiased, up-to-date information and combats systemic racism and health inequity.

“The goal is to move away from teaching that’s race-based, sexuality-based or biased in other categories where we could end up stereotyping our patients or contributing to systemic racism and health disparities,” Dr. McCallister says.

To formalize that revision process, the task force has adopted the “The Upstate Bias Checklist: A Checklist for Assessing Bias in Health Professions Education Content” developed by bioethics expert Amy Caruso Brown, MD.

The college’s curriculum working group also will soon be partnering with expert educator faculty, Dr. McCallister says, to help them use that systematic checklist tool and provide additional faculty development, oversight and review.

“Faculty have risen to the challenge and are personally investing in making positive change, incorporating their own revisions and using the checklist in classroom and in small-group discussions to make thoughtful revisions,” Dr. McCallister says. “They’re saying, ‘I need to step outside my comfort zone and be willing to hear someone else’s experiences and engage in behaviors that will make this a better place.’”

Adopting new curriculum

All-new curriculum addresses these issues, too — as early as students’ first year in medical school.

All-new curriculum addresses these issues, too — as early as students’ first year in medical school.

“Racism, Health, and Healthcare Delivery” is a new, one-week experience for first- and second-year medical students, and the four-week elective “Advanced Medical Ethics: The African American Experience” gives fourth-year medical students a deeper look at how to care for their Black patients.

A unique module also became available for first-year medical students in March 2021. Led by current students, “Race-Based Medical Misinformation: History’s Impact on Today’s Medical Practices” focuses on what the students identified as a major contributing factor to racist medical practices: falsehoods within medical education.

“After going through our first year of medical school, we experienced firsthand how our lectures lacked in-depth discussions about racial health disparities,” says Hafza Inshaar, one of three MD candidates in the class of 2023 who developed the new module.

“The omission highlighted the importance of revising our curriculum so that all trainees are provided with the education to become knowledgeable and compassionate physicians.”

Inshaar, Abbie Zewdu and Deborah Fadoju developed the new lecture as second-year medical students during the summer of 2020, designing a teaching module that includes a recorded lecture discussing origins of various medical myths, and small group activities to engage students in thought exercises. A pre- and post-lecture survey evaluates students’ knowledge and attitudes about racism and racist beliefs within the medical field as well as the impacts of those beliefs.

Several Ohio State College of Medicine faculty members, including Philicia Duncan, MD, and Valencia Walker, MD, helped the students refine the module.

“We hope that our efforts will not only spur long-overdue discussions regarding the impact of race on patient care, but will also inspire significant curricular change,” Zewdu says.

Enhanced support

For many years, students in the Ohio State College of Medicine were randomly assigned faculty coaches to help advise their professional development and career portfolios. Beginning in the 2020-2021 school year, students with Black/African American and Latinx/Hispanic backgrounds can also be assigned faculty mentors from similar backgrounds, says the program’s coordinator, Joanne Lynn, MD, associate dean of Student Life at the college.

“We matched interested Black and Latinx incoming first-year medical students with a faculty mentor in same-gender, same-race/ethnicity pairs,” Dr. Lynn says. “The volunteer faculty mentors were given mentoring guidelines, with one goal that they should meet with their students (virtually or in person) at least once a month.”

Many of the students benefiting from the pilot program explained that sharing this background with their mentor allowed them to be more vulnerable and connect on a level that ensured even greater support.

“As a minority student first coming into medical school, it can be difficult to express concerns or fears, as you don’t want to come across as overly sensitive or not a team player,” says Janine Bennett, an MD candidate in the class of 2024. “Having a mentor you connect with sort of serves as a safe space that you can be free and open.”

Amanda Martinez, another class of 2024 MD candidate, noted that, as a Latina student from out of state, a mentor from a similar background helped her transition to Midwestern life.

“My mentor has helped me navigate my first winter experience, transitioning to out-of-state life and living away from my family, and has provided outlets within Ohio where I can connect with other members of the Hispanic community,” she says. “This has helped me become comfortable in my new environment while also allowing me to retain a significant portion of my identity and sense of self.”

Reducing bias

The first step to mitigating bias is recognizing that it happens.

An implicit bias training developed at Ohio State has become a model for medical school admissions across the country. But the Ohio State College of Medicine Equity and Anti-Racism Task Force is now analyzing ways to apply that training more broadly.

“We’re partnering with the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity to evaluate the college’s culture and perform a needs-based assessment, meeting in small groups with students and staff,” Dr. McCallister says. “This will help determine how they partner with us in the next academic year to provide workshop-based faculty development sessions.”

Clinical evaluations, too, are being reassessed.

“Clinical evaluations in an MD student’s third and fourth years have a profound impact on their academic standing and their potential to match to their residency of choice,” Dr. McCallister says.

Ohio State’s Michael V. Drake Institute for Teaching and Learning is helping the College of Medicine task force complete qualitative analysis on learning environments and student perceptions, including actions between students and evaluators.

A foundation for continual improvement

“Cultural change is always slow,” Dr. Rankin says. “But I believe we’re really seeing and feeling a difference. With a collective mindset of willingness to do things differently and better, these discussions will continue, and progress will continue. Penetration of true change takes time.”

Dr. McCallister points out that if the Equity and Anti-Racism Task Force has done its job laying foundational principles for anti-racism, its work will never truly be done.

“If we’re approaching this the right way, we’ll always be aware enough to identify something else that needs improvement,” she says.

It’s not just the foundational principles of the past year that allow for this continual change. As an early land-grant institution, The Ohio State University was entrusted in its founding to pursue academic excellence while serving and remaining accessible to the most vulnerable. Ohio State has long been dedicated to championing potential in the underrepresented and underserved.

“I’m of a generation of physicians that, when I was navigating medical school choices as an African American undergrad, it was common to be one of just a handful,” Dr. Rankin says. “And even when I came to Ohio State in 2002, I thought there was reasonably good representation because I was far from the only one here.

“Ohio State is not just jumping on the bandwagon to invest in diversity and anti-racist policies. This is not new to us. And if the college continues to use these guiding principles, then — by design — we’ll always be improving.”

2020-2021 Health Equity and Anti-Racism (HEAR) report

Changing the narrative: Partnering for justice in health and health care

Download the full report to read all the stories