Why am I donating blood to help COVID-19 patients?

Editor’s note: As what we know about COVID-19 evolves, so could the information contained in this story. Find our most recent COVID-19 blog posts here, and learn the latest in COVID-19 prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As an emergency medicine physician at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, I’m now helping COVID-19 patients in a somewhat unusual way.

Not by caring for them when they arrive in our emergency department complaining of COVID-19 symptoms, but by simply donating my blood.

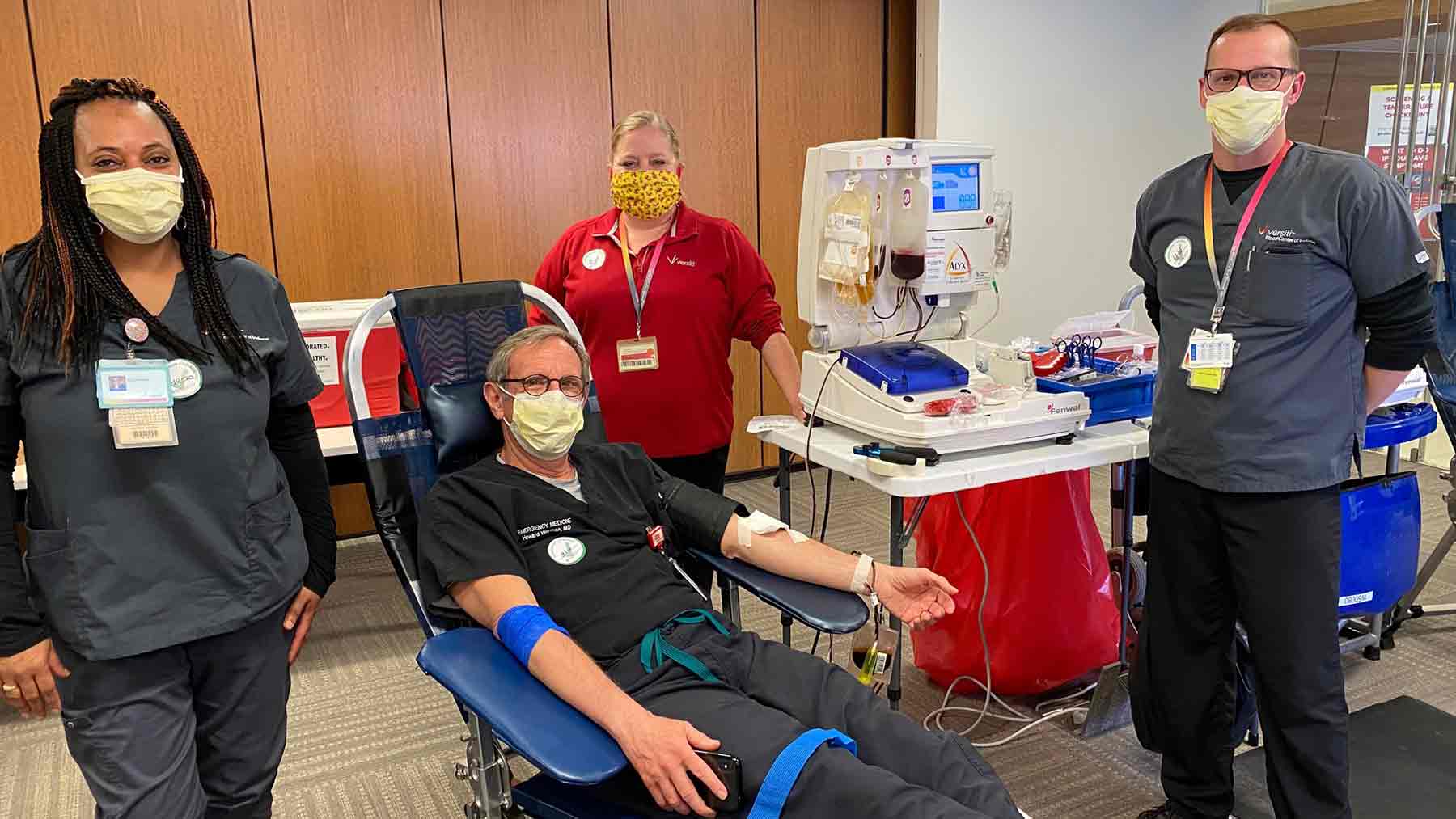

Earlier this month, I was the first person to donate blood for a new program the Medical Center is offering to treat critically ill COVID-19 patients. This is part of a nationwide effort to provide a portion of my blood—also known as convalescent plasma—as a potential treatment.

People like me who’ve recovered from COVID-19 often have antibodies—proteins in the blood—that could possibly attack the virus. Until a vaccine is developed, this is one of our best options for treating our most severely ill patients.

This actually isn’t a new idea. Convalescent plasma therapy has been successfully used to treat diphtheria, Ebola and even the Spanish flu that swept across the world more than 100 years ago. In this case, the convalescent plasma is being used as “compassionate use” therapy to boost the patient’s immune response to the virus and lessen the severity of the disease.

I’m not really sure how I picked up the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, but it may have happened while I was traveling in early March before shelter-in-place orders had been enacted. I was lucky and suffered only mild symptoms, including a respiratory infection, sore throat and body aches, for about 10 days.

After I was feeling better, I signed up to be part of a new program offered at Ohio State and other hospitals nationwide in which patients who have recovered from COVID-19 donate their blood. A simple blood test confirmed that I did indeed have the COVID-19 antibodies, and that I was no longer infected.

The decision to give blood wasn’t very challenging for me. Fortunately, I had a mild case and I’m able to give back to others simply by giving blood. It’s a simple and pain-free process that takes about one hour. I plan to donate more blood once a week, and each time my convalescent plasma will be transfused into one or two patients.

As part of our convalescent plasma program, Ohio State researchers will study the donated plasma to learn which antibodies perform best. The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center and more than 800 academic institutions and hospitals nationwide are working with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of convalescent plasma therapy.

The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center is partnering with Milwaukee-based Versiti Inc. to collect this much-needed plasma. Donors must meet blood donor eligibility criteria, and the collection center will confirm eligibility on the day of donation.

In addition, convalescent plasma donors must meet these criteria:

- Prior diagnosis of COVID-19 documented by a laboratory test.

- Complete resolution of symptoms at least 28 days prior to donation.

- Negative for HLA antibodies. Some women who’ve been pregnant, and males or females who’ve had a blood transfusion, will test positive for HLA antibodies.

I’m thankful to have the opportunity to participate in this research project to help save lives.

Howard Werman is an emergency medicine physician at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, professor of clinical emergency medicine at The Ohio State University College of Medicine and medical director for MedFlight.